Anyone following Roger Ebert on Twitter can attest to his consumption of books, blogs, and newspaper articles. But apparently he also reads every email that lands in his Movie Answer Man inbox—which is how the Kansas City (Mo.) Public Library (KCPL) initiated a film series collaboration with the Pulitzer Prize–winning film critic that has attracted cineastes for two summers. (Side note: Ebert generally frowns upon non-Answer Man-intended emails.)

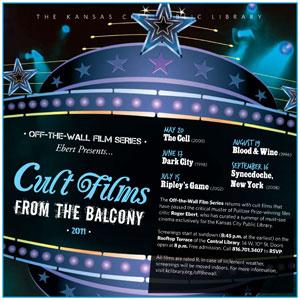

Since at least 2004, KCPL has programmed an annual outdoor film series during the summertime. Screenings take place once per month (from May through September) on the Rooftop Terrace at our Central Library, with films projected onto a white wall, hence its name: the Off-the-Wall (OTW) Film Series. A new theme every year helps determine film selections and keeps the marketing approach fresh. In 2010 and 2011, Ebert volunteered his time and expertise to choose the films for OTW, and in both instances lent his name to the themes: “EbertfestKC” in 2010 and “Ebert Presents … Cult Films from the Balcony,” which wraps up this month.

This collaboration started after I sent an email to the only address I could find for Ebert: his Movie Answer Man address. I didn’t expect a response (see: side note, above). Four months later, the library hosted its first Ebert-endorsed film screening—A Simple Plan (1998). Four months after that, Ebert and I sketched plans for the current 2011 series.

What does Ebert get out of this collaboration? He put it quite simply in a recent email: “It does my heart good to know great movies are finding great audiences with great screenings in Kansas City.”

The Evolution of a Film Series

OTW started with a simple premise: screening films on a big wall on the Rooftop Terrace. KCPL took the Off-the-Wall moniker seriously early on, showing incongruous films like The Bank Dick (1940) and campy 1950s sci-fi flicks. We averaged about fifty attendees for the first few seasons.

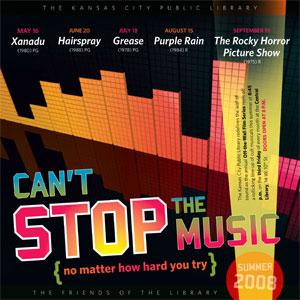

In 2008, the Off-the-Wall concept started to take off. Our “Can’t Stop the Music” films averaged more than one hundred filmgoers per screening. And we found our niche when our more adult-oriented screenings—Purple Rain (1984) and The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975)—accounted for more than half our total audience.

A postmortem assessment of the 2008 series led to a major shift in the programming priority for OTW films: not only did the final two films bring in more than 50 percent of that season’s attendance, but these crowds (based on my own observation) looked much younger than our typical audience. Here was the crowd of twenty- and thirty-somethings that every library wants. And so, more than showcasing our Rooftop Terrace as a unique venue, we decided this series would focus on this demographic going forward.

In 2009, the library established a partnership with Scott Tobias—film editor of The A.V. Club, whose New Cult Canon articles served as the theme. The “New Cult Canon” remains the most popular OTW season, with nearly eight hundred attendees that summer. And even better, that twenty- and thirty-something demographic is exactly what we got.

Ebert Enters the Picture

In 2010, “EbertfestKC” brought half the audience as the previous year (one heckuva thunderstorm contributed). Audience turnout was down—but the audience response was unlike any other film series that I programmed. Filmgoers consistently sought me out to say thanks for screening a film that they never would have discovered otherwise. And this is the entire point of the Ebertfest—the annual film series that Ebert hosts in his hometown of Champaign, Illinois.

Ebertfest was originally called The Overlooked Film Series, and every year it features a variety of films—documentaries, foreign films, Hollywood features, independents, and always one classic silent—that Ebert feels are worthy of larger audiences; thus the Overlooked designation. Though the name has changed, the philosophy remains the same. Ebertfest selections from the previous years (the thirteenth season in Champaign closed in April 2011) served as the foundation for the 2010 and 2011 OTW picks.

Our 2011 selections are doing well, with more than 350 attendees over four screenings thus far. Here again, the audience response is energizing.

Better to Ask for Permission than Forgiveness …

It should be noted that film licensing contracts/agreements—sometimes referred to as permission(s)—are an essential piece for all public film screenings. These contracts can be as simple or as frustrating as you choose to make it: though I am still searching for other film licensing vendors (and I know several librarians who are doing the same), the dominant options out there are Movie Licensing USA and the Motion Picture Licensing Corporation. Each one is essential, which is why the Kansas City Public Library (and many others) has contracts with both.

It is by far easier to work only within films made available by your contracts. But be advised of the following: 1) the film offerings from both companies are predominantly Hollywood studio films. If you want independent films, you will find some—but my bet is that you will discover the limits of your contract(s) pretty quickly. 2) The Movie Licensing USA database is not 100% accurate—especially when it comes to films released in the 1930s and 1940s; double check the production information and make a call to a customer service rep to double check—doing so can save you from a lawsuit (not exaggerating).

Film licensing becomes more difficult (and almost always more expensive) by pursuing a one-time screening license for a specific film. Movie Licensing USA has a helpful program that can save time and money—but you also have the option of contacting arts distributors (such as Kino International, which has a great collection of Nouvelles Vagues films) or individual production companies to secure a license for a film screening. The subscription service IMDB Pro is a great resource for obtaining the necessary contact information for production companies. It is possible that a sympathetic producer will grant your screening free-of-charge, but this is rare—and you should give yourself at least a six-week lead time for these negotiations.

What We Learned

Each OTW series imparted some lessons.

Do not discount the importance of grouping films with similar production values.

This will enhance the thematic coherence of your series and create a level of visual expectation for your audience. The first test of this theory was in 2008 with the “Can’t Stop the Music” films: Xanadu (1980), Hairspray (1988), Grease (1978), Purple Rain (1984), and The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975). Make no mistake: there is some truly bad cinema in here (namely Xanadu), and we tossed Grease into the mix as a calculated crowd pleaser, but there was a unity in rock-and-roll based soundtracks, bold color palettes, and a general reliance on musical-style set pieces.

The “New Cult Canon” films show a similar cohesion: They Live (1988), Near Dark (1987), Fight Club (1999), Donnie Darko (2001), and Battle Royale (2000). Despite the palpable 80s vibe of the first two selections, these films share a sometimes campy violent streak, a nihilistic attitude, and some inventive camera and editing work.

The 2010 “EbertfestKC” was among the most varied in my five-year tenure: a Hollywood crime film (A Simple Plan), an Australian comedy (The Castle, from 1997), a Sundance-winning documentary (American Movie, from 2000), a feel-good family feature (My Dog Skip, from 2000), and a light foreign drama (The Band’s Visit, from 2007). Ebert picked these five films as his favorites from the entirety of the Ebertfest line-up—which is a heckuva recommendation—but their all-over-the-map variety is programming more fitting of a five-day film festival than a five-month long series. Over five days, variety is a relief, whereas over five months this kind of variety appears disjointed.

Film programming can be a collection development tool.

Initially, the library did not have copies of this year’s Blood and Wine (1998), Ripley’s Game (2002), or Dark City (1998) available at KCPL. Only through a purchase made specifically for the OTW screenings were these films added to our collection. (The library always makes a new DVD purchase for a film screening, whenever possible, rather than relying on a circulating copy that may have been damaged.)

And here is an important value difference between those series derived from Ebertfest and the A.V. Club’s New Cult Canon: Ebertfest also provides value to the KCPL collection by bringing into it some critically acclaimed films that lacked mass appeal, whereas Fight Club and Donnie Darko were already readily available to patrons. [Note: This is not a criticism of Tobias or his New Cult Canon series—but is rather a criticism of my film selections based on his column: especially as his New Cult Canon series has aged, Tobias recommends some truly bizarre and below-the-radar material that would surely broaden any library collection.]

A programming series (be it film or otherwise) can develop its own unique mood or rhythm.

OTW is radically different from our more standard film programs, usually anchored by a monthly theme that screens twice a week in an intimate theater built inside a former bank vault. The OTW films all need to feel like an event, and the goal is to bring audience members multiple times in one season. The more typical film series has a different mission—oftentimes spotlighting an actor (like Frank Sinatra) or a director (like Spike Lee)—so the visual consistency and shared production values are more difficult to achieve in this setting (unless you are dealing with an auteur like Douglas Sirk), and most audience members will not attend all seven or eight films within such an abbreviated timeframe.

Do not let the audience choose between Bubba Ho-Tep (2002) and Raising Arizona (1987).

I have never understood the concept of letting an audience vote, which happened on occasion early in the OTW life cycle. If you are a programming librarian, do not cede responsibility to your audience (especially if you have not vetted all the choices): if the vote is a close one, you have succeeded in alienating about half your audience.

Adapt to your environment.

The OTW films are screened outdoors on an urban rooftop—there are condos all around, a bar with a rooftop deck one block over that occasionally hosts obnoxiously loud bands, jets for the annual air show practice overhead in August, and traffic always echoes up from the street. This is not a setting appropriate for a European art film—or any film in which it is crucial for the audience to catch every whispered word. This is an important reason why bold, campy, B-movie films succeed in this space.

Take a chance.

Sneak in an unexpected or unusual choice into your film series—the last slot in the schedule is often the best place for a risk-taker, but anywhere will work. For example, the OTW film for July 2011 was Ripley’s Game, which was never released theatrically in the United States. Zero name recognition, but star power in John Malkovich—though he’s not exactly a blockbuster actor. But afterwards, the audience that night gushed about Ripley’s Game. A John Hughes–oriented film series recently ended with Newport South (2001), a little-known film that Hughes produced that fit with the title for the series Inventing the American Teenager.

It doesn’t hurt to ask.

Even the most influential film critic in the country is so excited about showing audiences overlooked gems that he will not only volunteer his expertise, but will follow a meeting with Oliver Stone and Michael Douglas at the Cannes Film Festival with an email press interview promoting your collaboration. (Another side note: We learned not to put Roger’s face on a promotional flier—folks immediately ask whether he is coming to the library, and then they look incredibly disappointed.)

Finally, I learned that while it is a lot of fun to watch Fight Club (1999) for the tenth time with 250 of your peers (who are also watching it for the tenth time)—it is far more rewarding on all sides to watch The Cell (2000) and Dark City (1998) with one hundred dedicated library filmgoers who have never seen anything quite like it. And when the audience also gets a connection to Roger Ebert, that is truly Off-the-Wall.