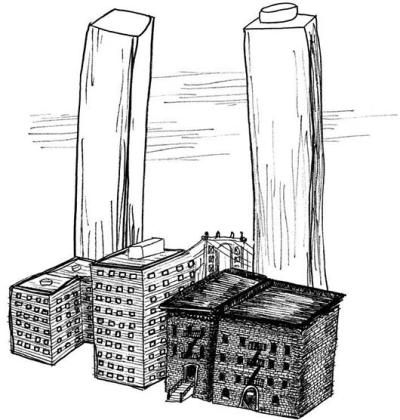

A brief look at the history of New York City’s Lower East Side (LES) reveals that this little patch of land has always been an area ripe for intense debate. The portrayal of the neighborhood in books, film and other media is constant — the romance, horrors and bitter struggles. The LES is a place of rare historical significance, a community that has inspired generations of activists, radicals, advocates and new Americans to envision a better future.

With this in mind, New York Public Library's Seward Park branch embarked upon a series of events that fostered dialogue-driven programming about topical issues of local importance. It felt like the continuation of a long tradition. The attempt to live up to the past would prove to be quite a challenge.

Our three-part plan

My main focus was to ensure that the program would consider what was important to the community democratically. I decided that a series spread over the course of three sessions would work best:

- Session 1: A discussion of major issues important to Lower East Siders, with a vote taken on what is the most important issue in the LES at the end of the session.

- Session 2: Talking about the ins-and-outs of the said “most important issue.”

- Session 3: Finding solutions to problems cited within the issue discussed.

This way, we would not only talk about issues, but attempt to find answers. The library is, after all, a place to obtain information.

Our partner

From the outset, we had a hurdle: we needed to reach out to a large enough audience to ensure a diverse array of attendees. An anticipated difficulty towards this end was convincing people that the library is not just a place to retrieve information, but to discuss issues that are important to them and their neighbors.

The choice of our partner organization was, therefore, paramount. We ended up partnering with an old mainstay in the neighborhood — a settlement house that received significant patronage in the area and had a history of doing programming of a political nature. By partnering with this organization, we would ensure that our efforts reached a fairly large portion of the neighborhood. We would also be helping to dispel the notion that libraries aren't willing to host discussions of a political nature.

In the spirit of keeping the series democratic, we stuck to the three-part model cited above, with each session taking place one week after the other. Three polling stations were set up in the neighborhood (one at our branch, another at the reception desk of our partner organization, and a third at the reception desk of an organization similar to our partner). Participants were invited to write on a piece of paper what they felt to be the most important issue in the LES.

Round 1 (and our first blunder)

The library and our partner were surprised at the volume of interest in the program. No doubt, this was a result of a dual publicity effort undertaken by both organizations; efforts were also made to alert local block associations and NYCHA campuses about the program.

Many votes were cast, and the first session was packed with people who wanted to make a case for what they felt was the most important issue on the LES. It was truly incredible. Not surprisingly, affordable housing (and its attendant problems of affordability, displacement and gentrification) was identified as the most pressing issue for the community.

Now that the issue was selected, we had to be able to discuss it intelligently. This would require more than giving people the ability to vent. Certainly, people’s experiences and emotions around affordable housing were part of the conversation we wanted to have — but it was more crucial to be able to break down the issue into smaller problems that would allow for solutions to be identified. In order to discuss the issue with authority, we needed to introduce our patrons to people in the community who knew what they were talking about.

This brings us to a blunder on our part — the second session followed a mere week later. This did not give us a lot of time to find people who understood housing in New York City. Not surprisingly, it is a very complicated issue. So much of what makes housing so confusing is that federal, state and municipal policies entangle in such a way that it can be difficult to know what is possible and what is, for the purposes of our series, a mere pipe-dream. As I reached out to local organizations and personnel, I realized I had not left myself enough time to prepare. Replies to my inquiries were not forthcoming, and I was left with just my own ignorance and an audience who was expecting a certain caliber of discussion.

I quickly had to compile a presentation about affordable housing in NYC — at least the basics terms and concepts. Included were bits and pieces of information especially relevant to the LES. It was a truly exhausting process and not one I would recommend. That said, in the process of conducting research for the presentation, I learned a lot about affordable housing and was ultimately able to provide my audience with enough information to stoke a more informed conversation. In the end, it turned out that tenants’ rights were particularly important to my audience. This issue in isolation was enough to provide a focus for the third and final session.

By this time, an organization I had reached out to, the Committee Against Anti-Asian Violence (CAAAV), had responded to my inquiry about affordable housing. As CAAAV has a history of serving the LES and neighboring Chinatown as a tenants’ rights advocate, I asked if they would send someone to talk to my audience about concrete solutions in regards to tenants’ rights. They were nice enough to send an experienced staff member — and our third session was a success. Our attendees left feeling armed with knowledge to fight displacement, but, perhaps more importantly, they learned a lot about why affordable housing is such a tricky issue in NYC and why surmounting those difficulties sometimes seems next to impossible.

Round 2: A new partnership

By the time the series ended I was exhausted. Though I felt the program had been a success, I was worn out and over-exerted.

Before I could rest, however, patrons who had seen the flier for the series began to ask me questions: What is this series you’re doing? Does the library really do this sort of programming? Even though they hadn’t been in attendance, I was so grateful to answer: Yes, we do this sort of programming. Before long, patrons who missed the first round were asking for a second.

The most persistent person asking for a second round was was a longtime patron of ours, Madeleine. She is a lifelong resident of one of the nearby NYCHA complexes and, unbeknownst to me, had a long record of working to organize NYCHA residents to be more active in attending zoning meetings and so on. Soon after, I was planning the second series.

Madeleine is involved with an organization called Lower East Side Organized Neighbors (LESON), one of many organizations that form a coalition called the Chinatown Working Group (CWG). The CWG was formed in 2008 to promote “[...] issues of shared concern throughout Chinatown including but not limited to affordability, preservation, revitalization and the social and economic well being of families, seniors and youths.”

Naturally, getting out information about inquiries such as where tenants can turn when being threatened with eviction, or how the zoning process works on the LES, are a major concern to the CWG. I felt the library ought to be a place where these tricky issues can be discussed. After Madeleine introduced me to her colleagues at the CWG, I felt a partnership was possible.

So far, we have continued the Community Conversations program with the CWG by way of two screenings — Marc Levin’s "Class Divide" and Prudence Katze and William Lehman’s "The Iron Triangle." Both films take a nuanced look at NYC neighborhoods and the impacts of development. Screenings were followed by two-hour discussions. Because the audience partially consists of people who have been involved in the CWG for years, questions often receive answers as well. People walked away knowing more than they did before they came. A sense of camaraderie was palpable.

And even though the CWG is not an old established institution, the word got out. We had around 80 people for our first session and 30 for our second. The publicity depended on how many members of the CWG had time to post fliers and spread the news — they were working on a volunteer basis, after all.

Upon reflection, this was an incredibly rewarding process. Certainly, this is what the library was made for — to provide information and serve to connect people from all walks of life to discuss issues common to us all. To have contributed to this vision at the Seward Park branch was thrilling. And I learned a lot, too.

Lessons learned

Now that I had completed a round of Community Conversations, I knew what questions to ask potential partnering organizations next time around.

First, I would be prepared with a pitch designed for organizations I approached for partnership. Organizations are generally willing to partner with libraries, but it’s important to consider not only the benefit to the library, but the benefit for the partnering organization as well. Although I had plenty of ideas, I wasn’t always able to articulate the incentives for other organizations. Understanding the opportunities for both institutions increases the potential for a successful and productive collaboration.

Second, I would research more into potential partners to determine the ideal opportunity for the organizations I am interested in. For instance, with larger organizations, sharing a series between two spaces can increase awareness about the program and demonstrate to attendees that both locations provide the potential for significant conversation. For smaller organizations, space can be a luxury — being able to provide a space and using it creatively can create a different type of atmosphere for a program. Knowing the size of potential partners and the scope of a program can help determine what questions to ask for future events.

Third, I learned some lessons about structure. To begin with, I needed to remember to pace myself. Momentum is good, but it is important to leave time to plan for each event if you intend to run a series. A weekly series was not practical. I also learned also that strictly democratically oriented programming can sometimes lead to a situation where everyone is asking great questions but nobody knows the answers. Sometimes having a topic where you know what is going to be discussed can be a good idea since you can get people in the room who know what they’re talking about. While the aim of hosting a truly grassroots, democratic series was thrilling, I feel the attendees of the second round left the events armed with more useable information.

Community Conversations continues to this day at the Seward Park branch. The branch also holds a monthly article discussion program where patrons are able to read an article chosen for its complex articulation of a topic. Topics have included the the economy, race, class and even the arts. While this series does not require us to partner with local organizations, it is a quick and simple way of talking about difficult issues with people who may or may not agree with your point of view.

All in all, the work carried out through the Community Conversations initiative has been some of the most rewarding work I’ve done so far. The series has provided a venue for finding out information about topics close to patrons’ hearts as well as connecting strangers over mutual struggles and hopes for the future — as a public librarian working in the Lower East Side, I can’t think of a better way to spend my time.

Andrew Fairweather is a librarian at the New York Public Library's Seward Park branch on the Lower East Side.