Editor’s note: This is the second in a special, week-long series on library programming for underserved, troubled teen populations, written by authors and a librarian who participated in the Great Stories CLUB.

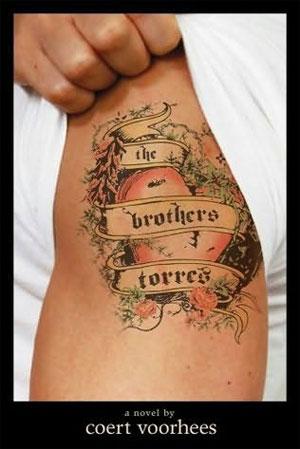

Earlier this month I had my first visit to a juvenile detention center. As part of the American Library Association’s Great Stories CLUB, my novel The Brothers Torres was selected (along with Jennifer Brown’s debut Hate List and Dope Sick by the incomparable Walter Dean Meyers) for inclusion in this year’s theme “Second Chances.” According to ALA’s website, the Great Stories Club “is a reading and discussion program that targets underserved, troubled teen populations.”

I arrived about a half-hour before the event and was met at the front door of the facility by Mr. Williams, who lead me through a couple locked doors and into the room where I’d be reading. We were soon joined by Stephanie Wilkes, the librarian; Lamar Anderson, head of education; and Mr. Elliott, director of the center. I was grateful for a few minutes to talk about the facility. They were (deservedly) proud of the place.

I learned that the kids ranged in age from thirteen to seventeen. It was generally a short-term facility, although some kids were there for three months or more. They’d been detained for offenses as varied as skipping school to fighting or armed robbery. In a number of cases, the kids received better care in the facility than they did at home. Also, they completed their school work during the day, and they generally left the facility having caught up or surpassed their classmates in school.

Then the kids shuffled in, girls first, followed by the boys. Ms. Wilkes offered a wonderful introduction of me and of the Great Stories CLUB, and then we were off. I read a chapter from the book, and I spent the rest of the hour answering questions and signing books. Mr. Elliott and Mr. Anderson took me on a tour of the facility afterwards, followed by cake, with a message on the icing that read, “Green Oaks JDC Welcomes Coert Voorhees.” Ms. Wilkes apologized that the cake had been pre-sliced, rendering the message slightly illegible, but knives weren’t permitted in the facility. Needless to say, this issue was generally not a problem at my other school visits.

During my reading, I couldn’t help but feel slightly uncomfortable as I read a passage about a party spot the narrator hoped to visit now that he is a sophomore: “There’s such a huge network of narrow dirt roads and hidden nooks and crannies that the cops can hardly ever find the festivities, let alone bust them up.” I was acutely aware that I was in the presence of actual cops who had busted up actual festivities—and actual kids who might have had their festivities busted up by these cops.

My favorite part of the evening was the Q&A that followed the reading. Once we got the basics out of the way—I didn’t make a billion dollars on the book; I don’t really have the tattoo that’s on the cover; no really, I swear I didn’t make a billion dollars on the book—we got into a good discussion about goals and dreams and writing.

We talked about what it means to be a writer, and one of the kids asked how to become one. My response to the question was (and is) simple: A writer writes. That’s it. If you want to be a writer, and you sit down to write, then by definition you are a writer. There’s no need to have other people validate you—you’re a writer. I said that the key to writing is exactly what it is for every other profession: you have to show up to work every day.

We talked about having dreams, about finding what it is we wanted to do with our lives, no matter how long it takes, and I shared with them the experience that made me realize I wanted to be a writer.

In one of my many previous eras, I was convinced I was going to be an actor. After majoring in theater (and Spanish), I moved to Los Angeles and got my headshots and started auditioning for roles in student and indie films, along with the occasional commercial. It didn’t take long before I realized that everyone in the waiting room, all the different versions of me waiting to audition, wanted to be there more than I did. Don’t get me wrong, I wanted to be an actor, but there was something in their eyes that told me they were willing to do whatever it took. I was surprised to discover that the same was not true for me. One thing was clear: I needed to find what I wanted as much, if not more, than anybody else. It took me a while, but writing is where I ended up.

Toward the end of the program, one of the boys in the back raised his hand and asked, “Why are you here talking to us?”

I stumbled a bit with my initial answer, trying to explain the process behind the Great Stories CLUB and how that led me to Green Oaks, but then judging by the look on his face, I realized that he wasn’t asking for the administrative details about my visit. In much the same way teachers zone out when students give a plot summary of a book instead of saying what a book is about, this boy’s eyes glazed over as I got lost in the details of the grant-funded program.

Me being there talking to them was the whole reason for sitting down at the computer in the first place. Not them specifically, of course—I didn’t write the book with juvie kids in mind—but readers in general. As writers we don’t dare presume that what we write is going to have an impact on other people’s lives, if for no other reason that presuming you’ll have an impact is the quickest way to ensure that you DON’T have an impact at all. When it actually happens, when I’m actually privileged enough to stand in front of a group of people holding my book, it makes all those solitary hours worth it.

That’s what I finally told the boy in the back row. That’s why I was talking to them, and why I’ll talk to any reader who’ll have me.

I signed their books, impressed that each one of them looked me in the eyes and addressed me as, “Sir.” And then it was time for them to get back to life “on unit,” as they called it, while I got to go out on the free.